By Andreas Ramos. Updated December, 2023

August Rodin may be one of the best-known artists in the world. Many of his art pieces have been duplicated, copied, parodied, and re-used in countless versions. Perhaps only the Eiffel Tower in Paris and the Statue of Liberty in New York City are equally well-known.

But there's something odd about Rodin's work: we look but we don't see.

The same with the Eiffel Tower: everyone "knows" it's the romantic icon of Paris, but that's not at all its original intention. It was a temporary structure for the Paris World’s Fair of 1889 to celebrate "...the art of the modern engineer, but also the century of Industry and Science in which we are living, and for which the way was prepared by the great scientific movement of the eighteenth century and by the (French) Revolution of 1789". Definitely not romantic!

As you'll see, I think Rodin's sculptures are deeply misunderstood. They're not what people think they are.

Stanford University has a large collection of Rodin sculptures. Gerald Cantor, who founded Cantor Fitzgerald, a large investment bank, gave his art collection to Stanford. Many pieces are open to the public; many more are in storage and can't be seen (incl. sculptures are even today are too scandalous).

I live next to Stanford and I'm on the campus almost weekly where I've often seen August Rodin's sculptures for the past twenty years, but only in the last few years, I began to wonder about them. There are many other spectacular art works on Stanford's campus, incl. Henry Moore's Large Torso, Alexander Calder's The Falcon, and Chihuly's Tre Stelle di Lapislazzuli, but nobody recognizes those or even pays attention to them. However, every tourist lines up for selfies with Rodin. Why do people recognize these art works and not others? Why do people like these so much? What, if anything, ties these works together?

Let's look at Rodin's best-know art works. What are the sculptures about? (I took the following photos).

Rodin's The Gates of Hell

Let's start with The Gates of Hell.

This was intended to be a large entrance to a planned Decorative Arts Museum (but the museum was never built). The gates are big: 6 metres high, 4 metres wide, 1 metre deep (19′ 8″ x 13′ 1″ x 3′ 3″). There are only a few copies of the Gates: in Paris, Bruxelles, Zurich, Mexico City, Tokyo, Dallas, Seoul, and Stanford.

There are more than 180 figures in the Gates. Rodin spent 37 years adding, arranging, and removing pieces. At the top, there are small figures of The Thinker and The Three Shades. The Kiss was also part of the Gates of Hell, but Rodin took it out and made it an artwork on its own.

Although the title is Hell, this isn't the Chrisitian hell. The sculpture is based on the a scene in The Inferno in Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy. The 180 figures swirl in chaos without direction. Many of the figures are in sexual positions, but a sex without passion. Many are grasping, clutching, or falling. Although there are many figures, they are alone, not interacting with others. Let's look at each of the main figures in the gate.

Rodin's The Three Shades (Les Trois Ombres)

These three stand at the top of the Gates of Hell. Rodin also made a large version of the group, which you see below:

They're called Shades, which is what the Greeks called the souls in Hades, the underworld (shades in Greek σκιά and in Latin umbra). This isn't the Christian hell; there is no god here; the shades are lost and without hope in Hades. The figures originally pointed to the phrase Abandon all hope, ye who enter here (from Canto III of the Inferno that was inscribed on an early version of the Gates of Hell).

The three shades are in a group but they don't stand together. Each is on his own, unaware of the other two. That's an odd idea for a group sculpture: one, one, one: not three.

You begin to see the idea in Rodin's work: people are alone, thrown in their own thoughts without connection to others. Before Rodin, the Christian world had a purpose and a vision. Rodin's world is bleak and solitary, which leads us to the main figure.

Rodin's The Thinker (Le Penseur)

We know The Thinker as a massive figure, but people are surprised to find the original is a small sculpture, only 70 cm (28 inches) tall.

Standing in front of The Gates of Hell, you look up to see the original small figure at the top, 6m above the ground (nearly 20 feet up). However, the figure was so popular that Rodin made the large version that we know (186 cm or 6 feet tall). Its heavy arms and legs make the figure look much bigger.

The original title of the sculpture is The Poet, which showed Dante speculating over the world he had created but later, the figure took on its own meaning.

The art work's English title is The Thinker, so of course we think he's thinking about something.

But the more you look at it, you realize he's not thinking. He's lost in melancholic rumination. He's not the Thinker; he's the brooder.

Art critics point out that his right elbow is resting on his left knee (which is an odd position), his fist covers his month (so he's not speaking), and there aren't pupils in his eyes (so perhaps he's blind). The sculpture's position is very awkward: try it yourself. But I don't think that's relevant.

Let's start with the figure's name. A thinker thinks about something. A sculpture of Einstein would show Einstein thinking at the blackboard, at his desk writing equations, or studying the universe, but it wouldn't show Einstein lost in a gloomy mood. The sculpture also is not the calm meditation of a Buddhist. Buddhism is release from the cycle of being, which is the opposite of The Thinker's despair. Rodin's sculpture is also not possible in the Islamic world, where Islam is a religion of direct relation between Allah and man and Muslims live in the Ummah, the community of believers. Sculpture in the USSR and China show heroic figures leading the way into the future. The figures in Rodin's sculptures have neither connection nor community. They are lost in melancholic brooding.

Here is the key point of Rodin: his figures look inward. They don't look at the world, they don't engage with the world, they don't even seem to notice the world or others. They are neither heroic conquerors nor tragic figures. They are alone, looking down, lost in their inner world of their feelings. Rodin was able to capture thes emotions in sculpture.

Perhaps this is why the Rodin sculptures are so popular. We can look at the statue of Admiral Nelson at Trafalgar Square, the statue of Napoleon at Les Invalides, Michelangelo's David, and many other monumental works, but we can't personally identify with them. However, everyone has had moment of doubt and loneliness; every person knows the chasm between people. Rodin's world is our Western world: no grand vision, each left to fend for himself. We recognize ourselves in Rodin's works.

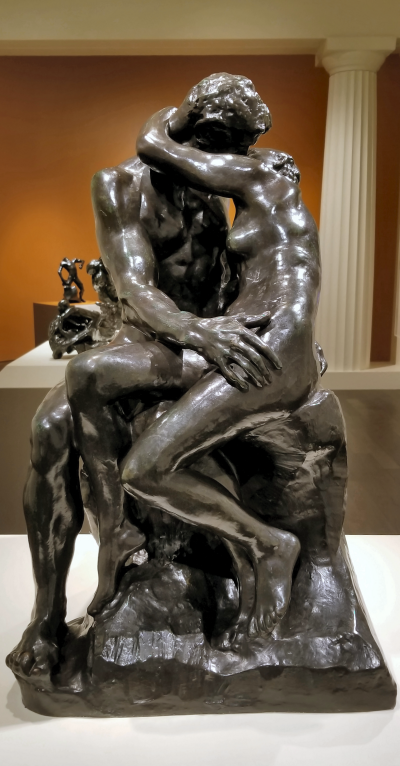

Rodin's The Kiss (Le Baiser)

Everyone loves this sculpture of tender lovers embracing in a passionate kiss.

The real story? In Dante’s Inferno, Paolo and Francesca are in the second circle of hell where they live in an eternal whirlwind in punishment for their sin. Why? Because Paolo read tales of courtly love to Francesca; they fell in love; they embraced to kiss, and just as their lips touched, Francesca's husband, who was also Paolo’s brother, entered the room, saw what was happening, and stabbed them to death.

Instead of a tender kiss, it's adultery and betrayal which ends in the murder of both. Awwww, how sweet!...

When the sculpture was made in the 1880s, the idea of two nudes in passion was shocking, even to Paris (!). For decades, it was hidden in sheds where only gentlemen of discretion were allowed to view it. It was only in the 1950s that it was opened to pubic view. Today, there's nothing controversial about it.

The piece was originally part of The Gates of Hell, but Rodin realized that it didn't fit with the Gate's overall theme so he removed it and made it a separate artwork.

Where other works by Rodin are solitary figures, The Kiss shows two lovers so intensely involved with each other that they don't hear Paolo, her husband, enter the room.

This captures a common human experience where we become so aware of something that we forget all else. Where the French of the 1800s saw the sculpture as disturbingly erotic, we see emotional closeness between two lovers.

Rodin's Bellona, Roman Goddess of War

Rodin made a sculpture of Rosé Beuret, his mistress, in one of her angry moods and entitled it Bellona Roman Goddess of War (1879), a furious godess of war.

But when you read her face, you realize she's not angry. Like other Rodin sculptures, her gaze is inward, despondent, and sullen in her sense of abandonment and isolation. This remarkable artwork captures complex inner emotions and makes them visible.

This is one of my favorite Rodin sculptures, and in fact, it led me to understand his other sculptures. It's hard to look at because she faces downward and you have to approach closely and look up to regard her face. She isn't looking at you, she is looking inward, and unaware that she is being seen, her emotions play across her face. The more I looked at this artwork, the more I realized what a difficult idea Rodin was presenting, and I began to realize his other works are also inward-facing.

Compare her face to the face of another famous French sculpture which was made at the same time: The Statue of Liberty (early 1870s) (currently in New York City, soon to be torn down).

The Burghers of Calais, another sculpture group by Rodin, shows six men led to their execution. They sacrifice themselves to save Calais. But instead of walking nobly or heroically to their death, they are in despair.

The Burghers of Calais are also at Stanford, where tourists cheerfully pose for photographs. Maybe that's true despair.

Let me know what you think of Rodin's sculptures and what I wrote. If you have a different opinion, I'd love to hear it. I'll add your comments here. Reach me at my contact page.

See Rodin's Art

The best resource is the Rodin Museum in Paris. He left his work to the nation of France.